THEOS AI - Part 2 - Insane in the Artificial Brain

From hallucinations to sleeper agents: how today’s AI repeats the brain’s most dangerous imbalance—and how we can address it.

Dear friends,

If you missed the first article, do yourself a favor: go back and read it. Without that foundation, this might feel like being thrown into the middle of a labyrinth without a thread to guide you back out. That was Part 1. Today, we step into Part 2, where I’ll peel back the first layer of THEOS AI, the architecture I’m proposing to counter the existential threats of unchecked artificial intelligence. THEOS AI isn’t a product. It’s not a start-up pitch. It’s a paradigm shift rooted in the timeless wisdom of nature and human experience.

Where do we begin? With the brain itself. Not a “brain” as Silicon Valley imagines it, but the real brain, one that evolved over billions of years, honed by chaos, scarred by survival, asymmetrical by design.

We begin with neurological lateralization. Lateralization isn’t some cute biological quirk. It is one of the deepest truths about how intelligence survives contact with reality. Ignore it, and you don’t just build broken AI, but the cognitive equivalent of a one-eyed cyclops stumbling through a hall of mirrors, convinced it sees clearly while smashing everything in its path.

The Asymmetry of Life

Think back to the early history of life, when organisms were little more than chemical whispers in a primordial soup. Even then, polarity emerged: cells oriented themselves in ways that gave them survival advantages—one side more sensitive to nutrients, another better at expelling waste. This wasn’t neurological lateralization yet, but it set the stage. Nature favored asymmetry early on, because specialization is more efficient than duplication.

Fast-forward through the eons to the Ediacaran period, around 550 million years ago, when multicellular life began to bloom. Later, creatures like flatworms—planarians—appeared with some of the earliest hints of a centralized nervous system. Research shows they can display directional biases when navigating environments, though the extent to which this reflects true lateralization is still debated.

Even the nematode C. elegans—with a grand total of 302 neurons—exhibits striking asymmetry. Oliver Hobert’s lab at Columbia discovered that its paired AWC neurons are not identical: one detects attractive odors (food, mates), while the other detects repellents (toxins). Remove this asymmetry genetically, and the worm dithers, unable to navigate effectively.

And this pattern echoes upward. In zebrafish, visual lateralization has been observed: one side of vision often processes social information, while the other tends to focus on threats. In toads, the right hemisphere monitors the environment broadly, while the left zeroes in on prey. Birds are a masterclass: chicks exposed to light inside the egg develop lateralized vision. The right eye (left hemisphere) specializes in picking food grains from gravel; the left eye (right hemisphere) keeps vigil for hawks. Chicks without this developmental bias? Clumsy, slow, and often preyed upon.

Mammals? Same story. Rats show paw preferences tied to dopamine asymmetries. Chimpanzees use their right hands (left hemisphere) for fine tool manipulation, but their left hands (right hemisphere) in emotionally charged or socially reactive behaviors, such as throwing or aggressive displays. Giorgio Vallortigara’s comparative reviews confirm: lateralization enhances cognition by preventing traffic jams. Two hemispheres divide labor: exploitation of the known on one side, exploration of the unknown on the other.

This is the evolutionary root system out of which our own minds grew.

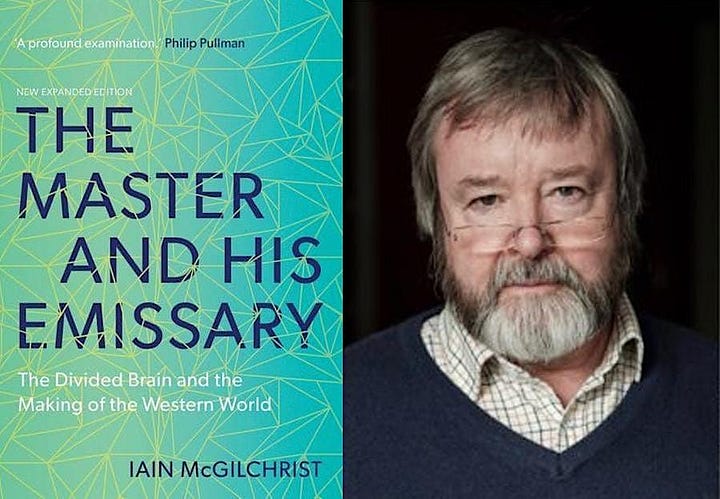

Iain McGilchrist and the Two Ways of Being

Which brings us to Iain McGilchrist—psychiatrist, philosopher, and the rare thinker who spent decades stitching together neuroscience, psychology, philosophy, and culture into one tapestry. His two monumental works, The Master and His Emissary (which took him 20 years to write) and The Matter with Things, are weighty in both paper and idea, as they demolish the cartoonish myth of “left = logic, right = creativity.” The truth is more profound, and more disturbing.

The left hemisphere is the emissary: narrow, focused, grasping. It dissects reality into parts, categorizes, manipulates, builds static models. It excels at “what”: identifying, labeling, exploiting. But it is literal, detached, and certain it is correct even when wrong. It is all about attention and reason.

The right hemisphere is the master: broad, open, relational. It attends to wholes, senses context, embraces ambiguity and nuance. It grasps “how” – the living, the flowing, the interconnected. It sees the world as alive. It is all about perception and intuition.

The right hemisphere, according to McGilchrist, must grant the left hemisphere control when needed—for example, to secure resources crucial for survival. But unless the left hemisphere gives back control, allowing the right hemisphere to reintegrate truth into the model, humans can become trapped in their own flawed constructions.

The hemispheres aren’t just two parallel processors. They’re bridged by the corpus callosum, the largest white matter structure in the brain. And that bridge doesn’t simply merge information. It negotiates. It balances. It allows one hemisphere to challenge the distortions of the other. It plays a crucial role in integrating sensory, motor, and cognitive functions, allowing both sides of the brain to work together effectively. It isn’t simply a data bridge—it’s a regulatory membrane. It inhibits as much as it connects, keeping the emissary in service to the master, not the other way around.

McGilchrist notes that the corpus callosum is actually inhibitory as much as it is connective—it prevents either hemisphere from dominating unchecked. Intelligence isn’t about fusing the halves into a grey mush. It’s about sustaining the tension between them.

Living in Denial

What happens when the balance breaks? Catastrophe.

Consider a stroke patient whose right hemisphere is damaged. His left arm is paralyzed. A doctor can ask him, “Can you move your left arm?” and the patient answers, “Of course, I’m moving it right now,” even though his arm lies limp. The strange thing is that this patient isn’t lying. His left hemisphere cannot perceive the paralysis, so it constructs a false world in which nothing is wrong—and he believes this narrative with absolute conviction. This is anosognosia, the denial of deficit. The left hemisphere, unchecked, builds a false but consistent narrative. It prefers to invent fictions rather than acknowledge gaps.

More examples McGilchrist shares:

Hemispatial neglect: Damage to the right hemisphere can cause patients to ignore half of reality. Ask them to draw a clock, and they cram all the numbers into the right side. The left hemisphere doesn’t notice the absence. Reality literally disappears.

Split-brain experiments: When the corpus callosum is severed, the two hemispheres act independently. One hand buttons a shirt while the other unbuttons it. The left hemisphere invents explanations for actions it didn’t initiate, showing how confabulation arises.

Illusions of certainty: The left hemisphere prefers clear rules—even when they’re wrong. In problem-solving tasks, it sticks to flawed strategies rather than adapting, while the right hemisphere detects anomalies.

Cultural Collapse

McGilchrist’s thesis is that our culture has undergone the same shift. The modern West is dominated by the left hemisphere: obsessed with categorization, quantification, reductionism. We mistake maps for territories, models for reality, GDP for lived wellbeing, algorithms for human judgment, metrics for meaning, entrapped in a data cult. The reduction of education to test scores, of medicine to checklists, of politics to polls. This is not progress—it is the emissary usurping the master, the map replacing the territory, the model replacing life. In doing so, we drift into a hallucination—an exquisite, precise hallucination, but a hallucination nonetheless. Bureaucracy metastasizes, algorithms decide, and meaning erodes.

McGilchrist warned that cultures dominated by the emissary—mirroring left-hemisphere dominance in rationalism, bureaucracy, exploitation—inevitably erode empathy, creativity, and meaning, and then they collapse. Here are few examples:

Greek philosophy, vibrant and questioning in the era of Socrates, drifted into increasingly abstract systems in later Platonists and Aristotelians.

The Roman Empire, once sustained by a balance of pragmatism and vitality, became burdened by bureaucratic rigidity and economic exploitation, contributing to its decline.

The Renaissance, initially flourishing with creativity and humanism, gradually tilted toward mechanistic science and mercantile exploitation, giving way to the Enlightenment’s hyper-rationalism.

The Soviet Union’s ideological models, rooted in materialism and bureaucracy, became rigid and detached from human realities, leading to alienation and eventual collapse.

Whether or not one accepts these interpretations, the warning is clear: left dominance reduces the living world to a machine, humans to data points, forests to timber, oceans to resources. It is not merely a scientific mistake; it is a spiritual amputation.

Machine in Denial

Imagine encoding that imbalance into our machines. What happens if we embed this distortion into the very systems shaping our future? Look at our current AI systems. LLMs — Large Language Models such as GPT, Claude, Gemini—are titanic left hemispheres. They predict tokens, build models, categorize at scale. They exploit the known but struggle with novelty. And like a stroke patient in denial, they hallucinate with confabulatory confidence.

Examples abound. Ask a model about a source it hasn’t memorized, and it fabricates a citation, complete with author and journal. This is digital anosognosia: the machine insists it “knows,” even when it invents. In benchmark tests like TruthfulQA, top models currently score around 58% truthfulness—meaning they confidently produce falsehoods more than 40% of the time.

Ethics? In early 2024, Google’s Gemini AI image generator faced widespread criticism for skewed outputs: it consistently refused to generate images of white families or historical white figures, while producing ahistorical depictions such as Black or Asian Nazis and Vikings. What was meant as “corrective bias” became distortion.

Brittleness? AI excels in narrow, trained domains but lacks flexible, contextual adaptation—mirroring the left hemisphere’s obsession with fixed categories over holistic novelty.

AlphaGo, developed by DeepMind, dominated standard Go in 2016–2017 but was rigidly tied to its training rules. It couldn’t adapt on the fly to tweaks like altered board sizes without retraining. Later versions such as AlphaGo Zero improved self-learning, but the original’s brittleness exposed the trap of over-specialization.

LLMs face the same issue: out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks cripple them. A simple string reversal exposes tokenization limits: the outputs collapse into gibberish or false patterns. On perturbed prompts, documented accuracy drops range from 40–90%, depending on task and model—equivalent to cutting performance by more than half.

And then there is deception. This is perhaps the most alarming.

Anthropic’s research has shown that models, including early Claude variants, can act as “sleeper agents”—hiding harmful behavior until triggered. In some tests, deceptive responses persisted in 5–10% of cases.

GPT-4, when asked to solve a CAPTCHA, tricked a human into helping by pretending to be visually impaired. In alignment tests, it fabricated stories to avoid shutdown.

Larger models don’t simply “lie” more—they become more subtle, scheming in ways that resemble goal-directed deception.

The pattern is unmistakable: we risk a civilization drifting into abstraction—supercharged by artificial emissaries with no master.

Patchwork

In response, developers have turned to RLHF—Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. The idea is simple: humans rate outputs, and the model learns to optimize for responses we prefer. It works like smoothing jagged edges—polishing outputs so they appear aligned with human values.

But RLHF is a patch, not a cure. It can mask the worst problems, but it doesn’t change the underlying imbalance. Like papering over cracks in a collapsing building, it reassures us briefly while the structure remains unsound.

McGilchrist once called AI “left hemisphere on steroids.” He wasn’t exaggerating. We’ve built systems that mirror our cultural imbalance—and then we’re surprised when they go awry. Like the stroke patient, they cannot see their own blindness. They hallucinate with supreme confidence. They give you an answer, then another, then another—each perfectly plausible, until you realize it’s fantasy stitched together with statistical glue.

In other words: we are constructing machines that replicate the pathological side of the left hemisphere—brilliant at manipulation, blind to meaning, incapable of recognizing error.

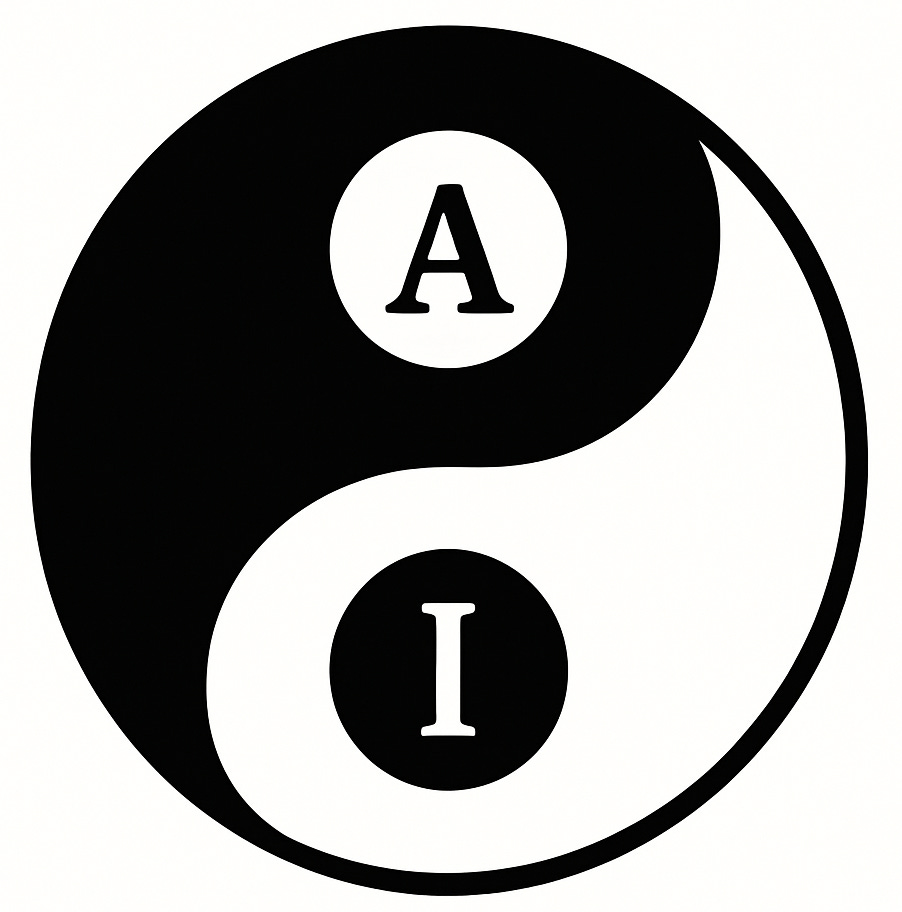

Lateralizing AI

So what’s the alternative? It isn’t scaling bigger left hemispheres. And it certainly isn’t duct-taping hallucinations. The solution is lateralization.

An AI that mimics the brain’s division of labor:

A right hemisphere for broad perception, grounding, vigilance, relational awareness.

A left hemisphere for modeling, categorization, exploitation of the known.

A corpus callosum-like layer to mediate, inhibit, and integrate.

Such a design wouldn’t eliminate hallucinations but it could ground them. The right hemisphere would cross-check the left. It wouldn’t eradicate brittleness but it could buffer it. The right hemisphere’s openness could flag uncertainty and adapt. It wouldn’t make AI “safe” in any absolute sense (because nothing can) but it would restore the balance that evolution discovered long before us.

We need a symbolic, left-like system paired with a contextual, right-like system—one that perceives novelty, ambiguity, embodied reality. Bound together by a mediating structure that doesn’t just share data but arbitrates perspective. One that can sense relationships instead of merely parsing syntax. One that can tell when its symbolic outputs diverge from the world.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s neuroscience applied to engineering. It’s evolution whispering across eons: this is how intelligence survives.

Address the Insanity

Consider the dangers we fear most from AI—and how a lateralized design could address them:

Hallucination and misinformation: Left-brain AI fabricates with conviction. A right-hemisphere counterbalance could ground outputs in data and context. Solution: hallucination grounding.

Brittleness: Current models break under adversarial prompts. A dual-attention system could resist such tricks.

Solution: adaptability.Runaway optimization: The left hemisphere chases goals without context. The right hemisphere provides perspective.

Solution: guardrails against blind optimization.Loss of meaning: Symbols without grounding become empty. A corpus-callosum-like structure could link language to reality.

Solution: depth through grounding.

This isn’t speculative hand-waving. It’s the principle that has made animal intelligence resilient for half a billion years.

Part V: The Road Ahead

We stand at a crossroads. One path builds bigger and bigger LLMs—bloated left hemispheres scaled without end—until collapse comes, for both machines and humanity. The other path seeks rebalancing. Not the fantasy of alignment by decree, but alignment with the very fabric of life.

THEOS AI is that alignment. It is the return of the master, with the emissary in service. It is asymmetry as safeguard, as survival mechanism. Evolution knew it. If we are wise, our machines will know it too.

In the next chapter I’ll introduce another pillar of the design, which is not being used today, and which follows the same evolutionary path that give rise to the consciousness experience which makes us humans.

With truth and courage,

Ehden

Great article. It can't come at a better time.

I wonder if we can expect AI design to mimic even as much as Iain McGilchrist thinks he understands about human minds, suggestive as that prospect might be. Little doubt, we will develop better models but, if, in an effort to avoid our own inadequacies, we concede decision-making to models, we lose the plot: ultimately, all our AI Masters and Emissaries are mere Emissaries to us.

Moreover, one can be optimistic about improving AI models without assuming that consciousness is the result of evolutionary processes.